Tackling Clinical Mastitis

Page 15 /

Gram Negative Bacteria & Other Pathogens

Gram Negatives: Escherichia coli and Klebsiella

Again, the caveat will be raised: you should discuss and develop all treatment protocols with your herd veterinarian.

The information presented here is for your learning purposes and should not constitute medical advice

That being said, there are some important pathogen-specific characteristics to know about the culture results you receive.

Gram-negative bacteria live in the environment of the cow. They are present anywhere there is manure. Infections with Gram-negative bacteria are a frequent cause of severe mastitis, although they can also produce mild and moderate cases. Cases of severe clinical mastitis are life-threatening — your veterinarian will likely act swiftly to treat these cows.

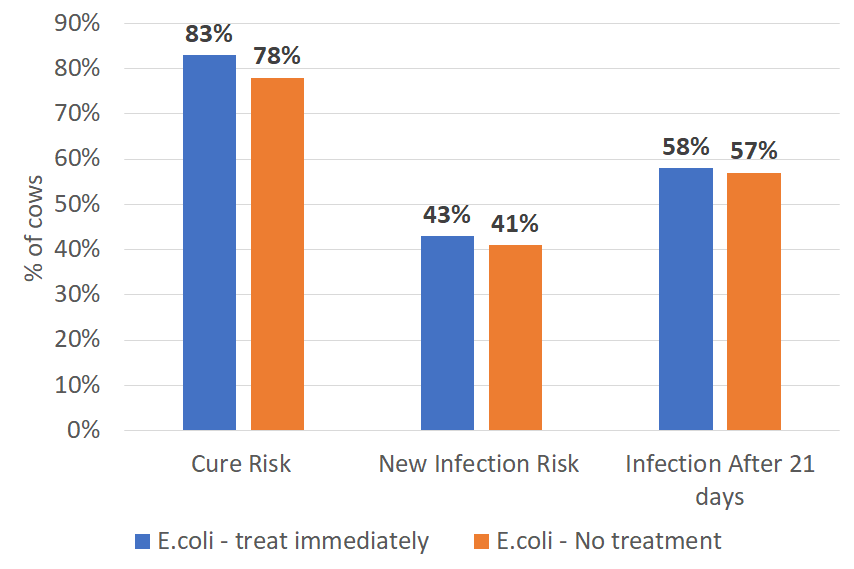

For the mild and moderate cases of clinical mastitis, there is good evidence to say that the infections will cure on their own — they don’t need to be treated with intramammary antimicrobials. The figure below illustrates the results of a research study, where there were no differences in cure risk, new infection risk, and chronic infections between cows with mild or moderate E.coli mastitis that were or were not treated with an intramammary antimicrobial medication.

Figure: Comparing cure risk, new infection risk, and chronic infection risk (infection after 21 days) between cows with E.coli that were immediately treated with intramammary antimicrobial medications versus those that were not treated1

The story might change when deciding whether or not to treat Klebsiella mastitis infections. Klebsiella is a Gram-negative bacteria that, like E.coli, is shed in the manure. It can cause very severe clinical mastitis, and can establish chronic infections after an initial clinical bout.

Recent research from the University of Wisconsin1 found that when non-severe clinical mastitis cases caused by Klebsiella bacteria were treated with an intramammary 3rd generation cephalosporin, bacteriologic cure was higher than untreated control cases1. Treated Klebsiella cases were resampled at 14 days and had a cure rate of 78%; whereas Klebsiella cases that were not treated had a cure rate of 18%. It should be noted that there was no other difference (e.g. SCC, milk production, risk of death or culling, mastitis duration) between the treatment groups… this is the part where the study stressed that more research is necessary to identify the specific cases of Klebsiella mastitis that may benefit most from antimicrobial therapy. Another finding of the study was that mild or moderate cases of E.coli mastitis DO NOT need to be treated with intramammary antimicrobial medications.

This study really shows us how knowing the bugs that cause mastitis can have a big impact on antimicrobial use on the farm.

Knowing what bacteria is causing mastitis will have a significant impact on the way in which antimicrobial medications are used on your farm

The Other Guys: Yeast, Prototheca, Mycoplasma

Collectively, yeast, Prototheca, and Mycoplasma do not respond to intramammary antimicrobial therapy. In the case of Prototheca (a type of algae) and Mycoplasma (a unique type of bacteria that does not grow on normal culture plates), the infections can be contagious, passing from cow to cow. As such, cows infected with Prototheca and Mycoplasma should be milked last and culled as soon as possible.

References

- Lago A., Godden S.M., Bey R., Ruegg P.L., Leslie K. The selective treatment of clinical mastitis based on on-farm culture results: I. Effects on antibiotic use, milk withholding time, and short-term clinical and bacteriological outcomes. J. Dairy Sci. 2011;94(9):4441–56.